Ernst Barlach (1870–1938)

Fluch (Blatt 1 aus: Die Ausgestoßenen), 1922 / Curse (Sheet 1 from: The Outcasts), 1922

In the large-format representation, Ernst Barlach puts his entire concentration on the person depicted. A bent older woman stands with folded hands in a hilly landscape. The passepartout section was expanded in the run-up to the exhibition, so that the entire printed area is now visible. However, a light edge is now also visible, which was created by the effect of light on the uncovered parts of the paper. The chalk lithograph is printed on a J.W. Zanders handmade paper, a frequently used paper of that time.

Anja Leistner, graphics restorer

Ernst Barlach (1870–1938)

Grablegung, 1917 / Entombment, 1917

Iconographically, the Entombment of Barlach is unusual and does not correspond to the Christian tradition of representation. Barlach shows here simple and poor people. A lamentation of the dead takes place here: In the center the kneeling and veiled figure, on the left a ‘fiddler’, on the right a blind beggar, both in diagonal axis to the central figure. At the right edge of the picture, in a slight top view and a view from above (for us viewers), the deceased figure lies in a shallow grave. Barlach’s wooden sculptures were highly valued for more than two decades. Of three wooden sculptures that the house acquired up to 1933, only this one could be kept from the confiscations by the National Socialists.

Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956)

Zottelstedt, 1918

Feininger turned particularly intensively to the relief printing technique of the woodcut within his graphic oeuvre. He depicts moods with contrasts between black and white. The influence of the paper character on the effect of the print was extremely important to the artist and he experimented with a wide variety of papers. He chose an exclusive Japanese paper for the graphic shown.

The sheet is exposed so that all inscriptions on it are visible.

Anja Leistner, graphics restorer

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945)

Frau mit totem Kind, 1903 / Woman with Dead Child, 1903

The drawing is part of a group of works from 1903 that deal with a mother’s pain and mourning for her dead child. The starting point for the intensive examination of the theme was the work on the cycle of prints on the Peasant War. Here, Käthe Kollwitz takes up the Christian pictorial formula of the Pieta, in which the dead body of her son lies in Mary’s lap. The motif is realized sensitively and touchingly: In the mother’s tight embrace the body of the dead son is completely embraced.

On the back of the sheet the artist has traced the drawing in rough outlines with red chalk.

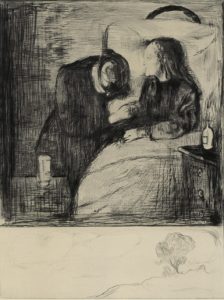

Edvard Munch (1863–1944)

Das kranke Kind I (aus: Acht Radierungen), 1894 / The Sick Child I (from: Eight etchings), 1894

Edvard Munch used the motif to come to terms with traumatic memories of his parental home. The girl, supported by a large cushion, shows her sister Sophie, who died of tuberculosis in 1877 at the age of 15. At the age of five, he had already had to cope with the death of his 30-year-old mother. Below the actual picture field is a landscape sketch with a single tree. The impression of the unfinished is what Munch wanted. The combination of the two different scenes combine the end of life with nature as a symbol for a new beginning.