»In the Dawn of the Republic«

100 Years Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz

»In the dawn of the young German republic«, as the founding director Friedrich Schreiber-Weigand recalls in retrospect, in 1920, the Chemnitz city council decided 100 years ago to establish a municipal art collection. Inspired by the idea of the museum as a place of democracy, education and participation, the administration, mediation and presentation of the city’s art holdings was recognized as an important municipal task in the first German republic. In addition to the establishment of the König Albert Museum in 1909 on Theaterplatz, the institutionalization of the collection in 1920 acknowledged the previously solely private commitment of the citizens of Chemnitz by the city councils.

2020 also marks the 160th anniversary of the founding of the Kunsthütte zu Chemnitz, the civic art association on whose collection initiative the museum was founded. On the occasion of this double anniversary, the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz are showing a representative selection of works of art of all genres and areas from the extensive municipal holdings in the exhibition »In the Dawn of the Republic«. The presentation tells the great and small stories of collecting, civic commitment, industry, art and craftsmanship, but also of the identity of a city marked by ruptures, in the web of European developments.

The exhibition is divided chronologically into five chapters from the 19th and early 20th centuries, through the post-war period and GDR to the present. In addition to the insights into the valuable collection holdings, the contemporary interpretation of the historical Gallery of Modern Art, which was developed in 1926 by Schreiber-Weigand together with Karl Schmidt-Rottluff as a display for contemporary art, is particularly noteworthy. In addition to its open-minded acquisition policy, this is one of the reasons why the museum enjoyed the reputation of being one of the most important German museums for contemporary art and especially for Expressionism in the 1920s.

The Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz can look back on a very varied history since its foundation as a municipal museum 100 years ago, in which many successful periods stand alongside less glorious moments. Alternating tensions, which shape the city of Chemnitz in an ambivalent way, also characterize the history of the art collections. Despite all the breaks, the art collections offered and continue to offer an aesthetic, artistic and historical continuity that was and still is an important element of the identity and also of the civic pride of the city and region.

#DeinMuseum

Supported by

Level 1

Romanticism

The art of the Romantic period is one of the focal points of the collection of the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz. The first acquisitions were made in the years following the founding of the Kunsthütte in 1860 and have been continued continuously. The initial orientation of the Chemnitz collection towards Dresden, a center of Romanticism, also played a role later. The purchase of Romantic and Biedermeier works was made possible by the sale and exchange of modern art, in particular the works of Expressionist artists, primarily during the period of National Socialism between 1933 and 1945. The collection was expanded extensively in 1966 and 1977 through the donations of the lawyer Dr. Helmut Brückner.

Caspar David Friedrich, Carl Gustav Carus, Johan Christian Dahl, and Heinrich Dreber, among others, are represented with paintings and graphics. In addition to Saxon landscapes, watercolors and drawings of popular Italian destinations by the artists form a focal point. Carl Wilhelm Götzloff, Adolf Gottlob Zimmermann, and Carl Friedrich von Rumohr show impressions of their journeys to Rome, San Gimignano, and Sorrento. Italy was the most popular travel destination in the 19th century. With its natural beauty and the buildings from different eras, the country was a source of inspiration. Still lifes, portraits, and the family and children’s portrait, which was first highly valued in this period, complete the insights into the valuable holdings.

Click here for the work comments in the Romanticism exhibition area.

Work=Prosperity=Beauty

The industrial city of Chemnitz was known as “Saxon Manchester”. City views by the two members of the Chemnitz artist group, Martha Schrag and Alfred Kunze, impressively show the rapidly growing industrial location, but also the social problems associated with it. Elegant silk fabrics from the heyday of the French textile industry, lace, ribbons, bows, and advertising posters reflect the luxury and prosperity of the epoch of the so-called “Gründerzeit”, and are at the same time a sign of the international networking of the local industry.

In the New City Hall of Chemnitz, there is the only remaining mural by Max Klinger, donated by the Chemnitz industrialist Hermann Vogel. The Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz own studies and designs in original size on cardboard. The title of the painting Work=Prosperity=Beauty stands for a basic attitude in the industrial city of Chemnitz: that all prosperity must be worked hard for and only then can one turn to beauty. At the same time, it is the title of this room, whose themes determine the dialogue between local and international representatives of the art of Impressionism and Symbolism.

Honoré Daumier addresses the position of men and women in society. His caricatures from the extensive donation of the Chemnitz entrepreneur Erich Goeritz are dedicated to the questions of equality that are still relevant today.

Click here for the work comments in the Work=Prosperity=Beauty exhibition area.

Carlfriedrich Claus Archive

Like hardly any other artist from the GDR, Carlfriedrich Claus was active in an international network of contemporary art and intellectual exchange. He was in correspondence with authors, artists, and philosophers from many countries and was involved in the aesthetic debates of his time. Around 1960 he was one of the co-founders of international visual poetry. The Carlfriedrich Claus Archive preserves the complete legacy of this exceptional artist and – on the basis of his diaries and manuscripts as well as the approximately 22,000 letters that have survived – provides a direct insight into the art processes of the second half of the 20th century.

The language sheets and sound processes of Carlfriedrich Claus and the numerous works of artist friends such as Raoul Hausmann, Bernard Schultze, Fritz Winter, Willi Baumeister, Gerhard Altenbourg, Michael Morgner, and many others as well as rare artist’s books, multiples, dedicatory copies, or manifestos illustrate the renewal efforts of that time. The concept of breaking down the boundaries of the media is now pursued worldwide and has lost none of its topicality to this day.

Level 2

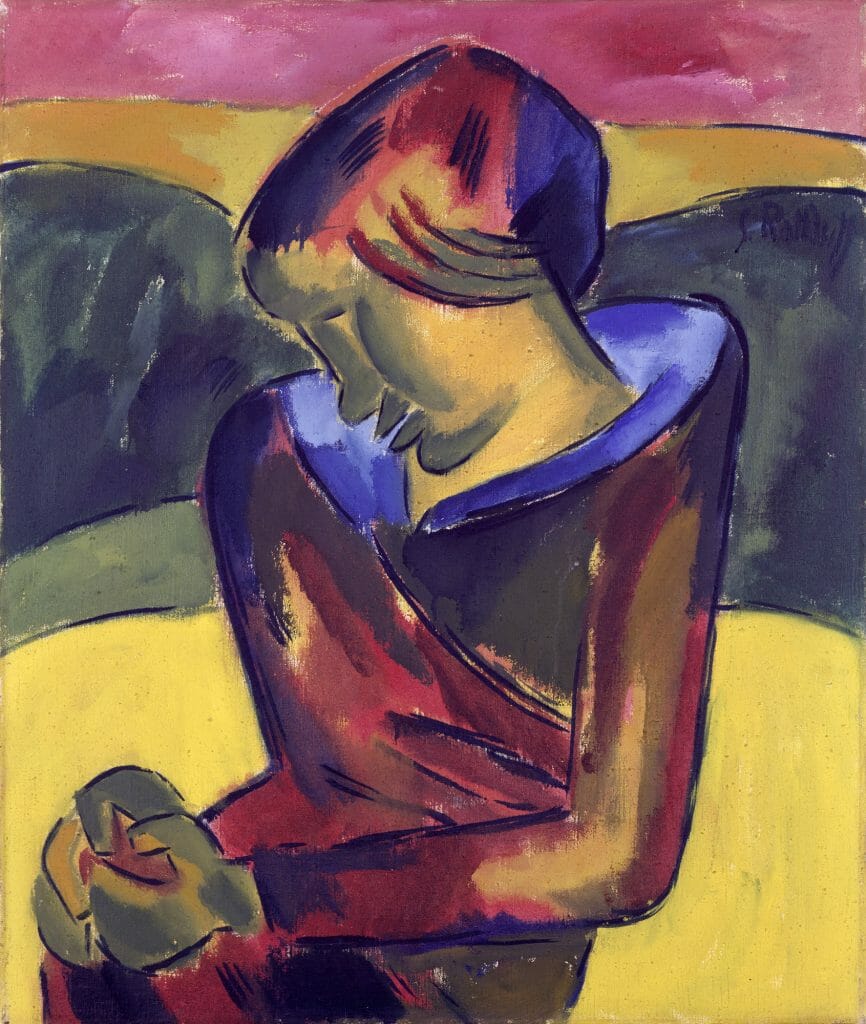

Artist group Brücke

The art of Expressionism occupies a prominent place in the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz. Besides the artists of the Blue Rider active in Munich, the Brücke was the most important group of Expressionist artists. It was founded in Dresden in 1905 by the architecture students Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The young artists wanted to express what “urges them to create”, “directly and unadulteratedly”, as their 1906 program stated.

Although the Brücke found its birthplace in Dresden, Chemnitz can probably be described as its nucleus. With the exception of Fritz Bleyl, all founding members grew up in Chemnitz, Schmidt-Rottluff was born here. The members of the group strove for new artistic paths and found in the name a symbol for the connection from one bank to another. The expression of a picture should show the artist’s interior. Bright and strong colors served as an important medium to express feelings in the picture. Many artists found inspiration in untouched nature as well as in non-European art and culture, for example from Africa and the South Pacific. In the field of graphic art, the material wood became a field of artistic experimentation: woodcut was the preferred means of expression alongside painting. Increasingly, the members distanced themselves artistically from each other and individual interests prevailed. In May 1913 the group of artists disbanded in Berlin.

Click here for the work comments in the Artist group Brücke exhibition area.

Expressionism and New Objectivity

Friedrich Schreiber-Weigand, the first director of the municipal art collection founded in 1920 “in the dawn” of the Weimar Republic, promoted the art of his time, especially Expressionism and New Objectivity, with exhibitions and acquisitions. Until his dismissal, after the National Socialists came to power in 1933, the Chemnitz Museum was one of the most important museums of contemporary art in Germany. Schreiber-Weigand maintained in close contact with Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The work of the Chemnitz-born artist is the focus of the exhibition area, which presents various examples of painting, graphic art, and arts and crafts.

In 1925, Chemnitz was the third stop after Mannheim and Dresden for the exhibition Die Neue Sachlichkeit (The New Objectivity), which gave the art movement its name. Paintings and photographs by artists of this epoch complement the expressionist works.

In 1937, more than 700 works of art from the collections were confiscated as part of the “Degenerate Art” campaign, after “unwelcome” works of art had already been sold. This makes the museum one of the institutions in Germany that has suffered considerable losses in the field of Classic Modernism.

Click here for the work comments in the Expressionism and New Objectivity exhibition area.

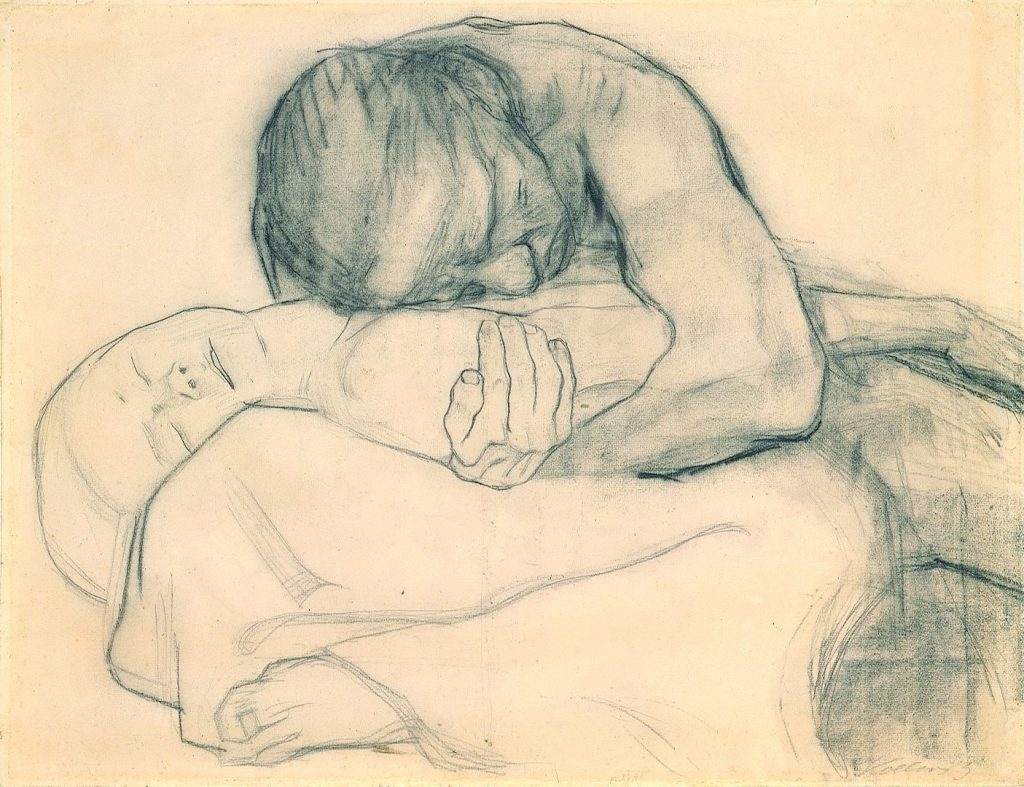

Formative contemporaries: Barlach, Kollwitz, Munch, Feininger

The representatives of so-called Classic Modernism are extensively represented in the Graphic Arts Collection. Ernst Barlach’s main theme was the existential loneliness of the individual. Even more so than Käthe Kollwitz, he had initially welcomed the First World War, only to later deplore it as a human tragedy. Käthe Kollwitz lost her son at the front. The traumatic event made her a consistent pacifist. Motherhood is one of the central themes in her work. Her motifs range between happy experience and the desperate pain of loss. Personal experiences with illness, pain, and the death of loved ones also had an intense influence on the art of Edvard Munch, who dealt with the death of his sister in the graphic The Sick Child. As a child, he also had to cope with the early death of his mother.

In the recent past, a special graphic treasure has been acquired: 298 printed graphics, watercolors, and drawings by Lyonel Feininger were purchased from private collections in Nuremberg in 2008. Feininger is one of the most important woodcutters of the 20th century in the field of graphics.

Caesura 1945

In the immediate post-war period, continuous collection activity was only possible to a limited extent. The museum building was severely damaged during a bombing raid on Chemnitz in March 1945. For this reason, the first presentations of works by Käthe Kollwitz and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff took place in the Schloßbergmuseum. In the first years after the war, many artists dedicated themselves to reflecting the immediate present and views of the destroyed cities. Thus Wilhelm Rudolph’s work shows the ruins of Dresden. His exploration of the subject is considered unique in terms of its scope and intensity. Paintings by Erich Gerlach, Hans Jüchser, Bernhard Kretzschmar, and Heinz Tetzner complete the exhibition area, which also includes works from the Textile and Decorative Arts Collection from the post-war period, which lacked funds and materials. These include the wooden animals by Artur Winde from 1947 and the dolls by Doris Wendt-Scheinert made of the simplest materials, such as the workgroups Flüchtlinge (Refugees) and Trauernde Eltern (Grieving Parents) from 1946.

Art in the GDR

The art of the GDR collected up to the fall of the Berlin Wall is multifaceted. Only to a small extent is the promotion of a rigid realism by the official cultural policy of the GDR reflected in the acquisitions of the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz. Nevertheless, mainly representational art was acquired during this period, for example by Will Schestak, Carl-Heinz Westenburger, and Lothar Zitzmann. The acquisition policy was characterized by acquisitions of art by regional artists. It was only many years after its time of origin that non-representational art, e.g. by Edmund Kesting, Otto Müller-Eibenstock, or Willy Wolff, was purchased. In addition to the art centers of Berlin, Dresden, and Leipzig, an independent and unmistakable art landscape was created in Karl-Marx-Stadt even without an art academy. Artist portraits by the photographer Christine Stephan-Brosch complement the painting and graphic art of the artists, most of whom live in the district. Art by the members of the Chemnitz artist group Clara Mosch and works by Rüdiger Philipp Bruhn, Carsten Nicolai, Klaus Hähner-Springmühl, as well as the graphics portfolio Das waren Landschaften (Those were landscapes) from the series ADREI convey the image of the unacademic, lively Karl-Marx-Stadt art scene in the 1980s.

Click here for the work comments in the Art in the GDR exhibition area.

Dialogues

Paintings and sculptures by artists from various art academies and with different stylistic influences enable dialogues between the present and past decades. Almost 50 years ago, Núria Quevedo painted 30 Years of Exile, referring to the community of Spanish artists and intellectuals who fled from Spanish fascism. This work formally corresponds in space with the manifold realistic expressions of Stephan Balkenhol, Georg Baselitz, Jörg Immendorff, and Markus Lüpertz. In addition, powerful painterly positions by Hans-Hendrik Grimmling, Michael Morgner, and Georg Pfahler stand their ground.

The latest acquisitions and donations are also presented: An installation by Henrike Naumann, which deals with the role of the artist in Socialism using the example of her grandfather Karl-Heinz Jakob and the perception of the GDR after reunification, textile light objects by the conceptual artist Daniel Buren, graphics by the artist duo M+M, and the firmly integrated glass window by David Schnell. The exhibition area continues to show art from the donation of Céline, Heiner and Aeneas Bastian, which considerably expands the spectrum of modern and contemporary art in the house.

Click here for the work comments in the Dialogues exhibition area.

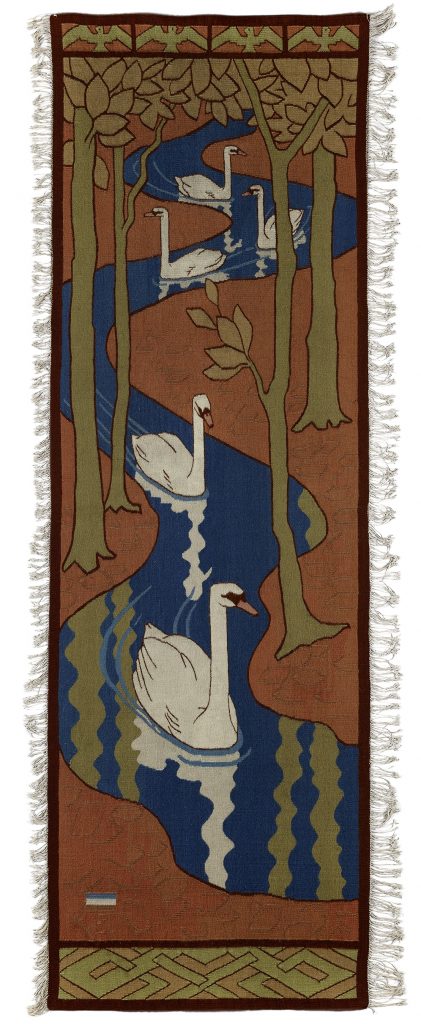

Collection Textile and Decorative Arts

Originating from the model collection founded in 1898, the Textile and Decorative Arts Collection comprises unique textiles of the 19th and 20th centuries. The focal points are Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Wiener Werkstätte, and Bauhaus. The collection also includes carpets, embroidery, lace, non-European textiles, wallpapers, Japanese dyeing stencils, artists’ posters, nature studies, and a large number of arts and crafts works. The aim was to present exemplary design to the local industrialists and artists organized in the Industrial Association and to provide creative inspiration.

To this end, with the help of the Chemnitz Industrial Association, decorative and upholstery fabrics from the textile centers of Great Britain, France, Austria, Germany, and Italy were collected and works by renowned designers such as William Morris, Charles Francis Annesley Voysey, John Henry Dearle, Georges Lemmen, Otto Eckmann, Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, Carl Otto Czeschka, Erich Kleinhempel, Mariano Fortuny, and Benita Koch-Otte were acquired. After the First World War, the Textile and Decorative Arts Collection, which was integrated into the Städtische Kunstsammlung in 1984, was continuously expanded so that today it contains 27,000 exhibits.

Click here for the work comments in the Collection Textile and Decorative Arts exhibition area.

Level 3

The Gallery of Modern Art

The foundation of the Städtische Kunstsammlung in Chemnitz in 1920 marked the beginning of systematic museum collecting activities. As a municipal institute the Städtische Kunstsammlung was located in the new museum building, along with the Kunsthütte. The founder-director of the Städtische Kunstsammlung was Friedrich Schreiber-Weigand, who had directed the Kunstverein since 1911 and continued to be active in this capacity as well. The agenda he formulated involved »giving the collection a form that would enable it to stand out among the up-and-coming new museums that had emerged as creations of a modern urban spirit.« After just five years, he had succeeded in acquiring more than 185 paintings and 26 sculptures by contemporary artists. In 1923 he also instituted a Graphic Art Cabinet. Despite the difficult economic situation, inflation and some ideological resistance, the Galerie der Moderne – a contemporary show of modern art – was set up on the 2nd floor, in collaboration with the artist Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Given the fact that the rooms used at that time were structurally altered over the course of the decades, in the current reconstruction (design: Enzo Zak Lux) of that Galerie, a coloured wall represents one of the former nine exhibition rooms.

Click here for the virtual reconstruction of the Galerie der Moderne.

Friedrich Schreiber-Weigand and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

When, Karl Schmidt left his place of birth, Rottluff, in 1905 after finishing secondary school so as to study architecture in Dresden, no one could have foreseen that twenty years later his artistic oeuvre would become the basis of a modern museum collection. Works by Karl-Schmidt-Rottluff were on show in the museum’s opening exhibition as early as 1909, alongside works by 200 other artists. In the 1920s he was by far the best represented Expressionist, ahead of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Otto Mueller, Max Pechstein and Emil Nolde. Nine paintings and numerous prints had entered the collection through donations and acquisitions. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff maintained a friendly correspondence with the museum director Friedrich Schreiber-Weigand, advising him on new purchases and sometimes drawing his attention to other artists. Although the artist lived in Berlin as of 1911, he visited his family regularly and also the

museum in Chemnitz. It was not surprising therefore that Schreiber-Weigand entrusted him with the task of designing the colour scheme for his new gallery concept.

The Colour Scheme of the Gallery of Modern Art

The collection was to be shown not as a wall-filling presentation, but as a single-row of works in neutral architectural surroundings. The aim was to underscore art’s aspiration to autonomy. This gave rise to the idea of adapting the colour of the walls to the respective works of art in the individual rooms. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff developed a corresponding concept. The walls must have been painted, in one colour for each room, around February 1926. As no precise documents or colour samples have survived from that period, our reconstruction of the colour scheme draws on newspaper reviews and reportages and black-and-white photographs; it is also oriented around the colours Karl Schmidt-Rottluff used in his paintings. At that time, Oskar Kokoschka was hung on cobalt green, Edvard Munch and Wilhelm Lehmbruck on light yellow. Ferdinand Hodler and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner on blue and Karl Hofer on brown. As many works from that era have been lost or were confiscated, this reconstruction tries to come as close as possible to providing a concentrated impression of the historical situation by means of the individual works that have been preserved along with representative substitutes. At the same time, it attempts a new interpretation of that situation.

Confiscations and Losses »Entartete Kunst«

Many of the works on show between 1926 and 1929 are no longer in the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz. Between 1934 and 1944 they were either defamed as »degenerate art« and became victims of prohibitions and confiscations, or else they were sold or exchanged. Today many of the works are in other museums and private collections; the whereabouts of some is unknown. It was possible to re-purchase Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s sculpture The Thinker and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff’s painting Autumn Landscape. A few of the works returned to the museum on permanent loan, for example, Oskar Kokoschka’s Self-portrait with Crossed Arms. The photo-montage based on historical photographs shows all the paintings and sculptures which were part of the holdings of the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz at the time. What could not be taken into account in this context are the equally extensive losses in the graphic art sector.

Directions